I discovered this wonderful deathbed portrait, which resides at the Manchester Art Gallery, in the book Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c.1500-c.1800

Sunday, September 28, 2008

"Sir Thomas Aston at the Deathbed of his Wife," John Souch, 1635

I discovered this wonderful deathbed portrait, which resides at the Manchester Art Gallery, in the book Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c.1500-c.1800

Saturday, September 27, 2008

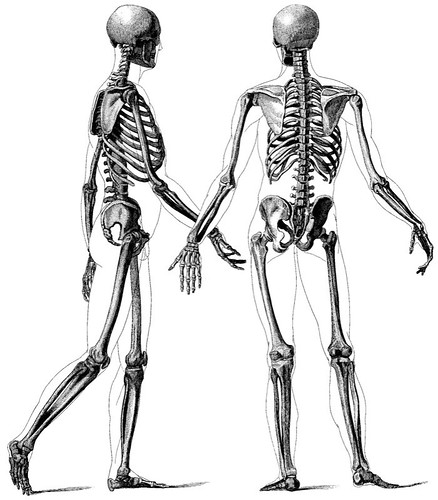

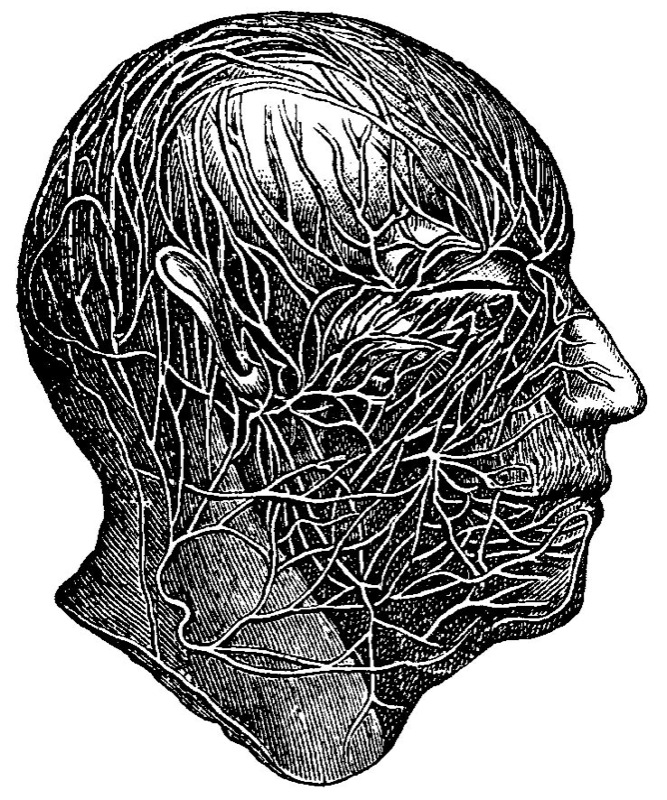

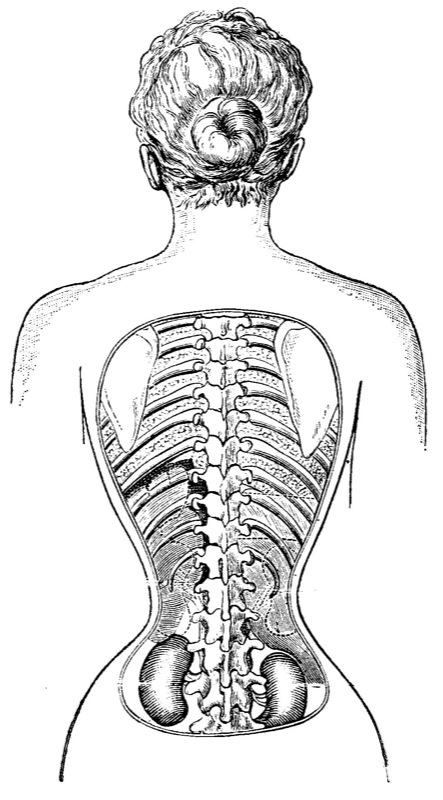

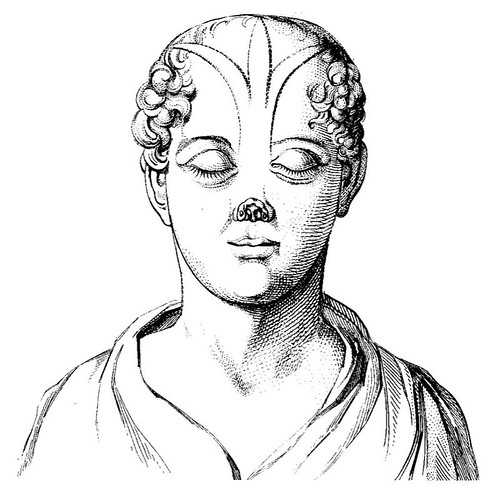

"Images of the Human Body," Pepin Press

All of the above images are drawn from the CD-ROM of anatomical images (with lovely illustrated book/catalog) I just picked up at the Wellcome Collection bookstore called Images of the Human Body.

These are just a very few of my favorite images in the collection; I have posted more of my favorites here. You can find out more about the book here.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Wellcome Collection, London

The Wellcome Collection of London--which I just visited for the first time a few weeks ago--is, hands down, my new favorite museum. The temporary exhibitions on display when I visited were wonderful--thought-provoking, beautiful, and engaging--and I spent a good hour there. The permanent exhibition--a collection of historical objects amassed by Henry Wellcome--made my head spin.

Called Medicine Man, the exhibition was in effect an abbreviated and re-conceptualized re-installation of a show I had seen years ago at the British Museum called Medicine Man: The Forgotten Museum of Henry Wellcome (which inspired this wonderful catalog.

The Medicine Man exhibit is in many ways an exhibit about collecting as a meaning-making activity and a collection as a form of portraiture. The size and breadth of the Wellcome's collection is well suggested by the ways in which the large accumulations of like-objects are grouped in the exhibit hall; you can sense the psychology and questing drive of the collector. Votives, vanitas, prosthetics, paintings, photographs, medical supplications, relics, the walking stick of Charles Darwin... Really a dizzying array of artifacts relating to mankind's attempts to understand and mitigate his relationship to death, disease, and the body. Also included was a wonderful filmic tribute to the collection by The Brothers Quay called The Phantom Museum, where we are allowed to explore vast storehouses filled with Wellcome's wonderful objects and watch their secret, animated life in the vaults.

All in all, it is exciting to see the Wellcome Collection carrying on in the tradition of their namesake, and exhibiting (and commissioning) a wide range of multi-disciplinary investigative works exploring the complicated realities of what it is to be a medical subject, an anatomical body, and a human being prone, as we all are, to disease and ultimate death. This is the most exciting museum I have visited in a long time, one committed to accessible but provocative works playing at the intersection of, per their masthead, Medicine, Life and Art.

More about the Medicine Man exhibit here and about the collection here. You can also see my own photos from my visit to the collection (from which the above are drawn) here.

If this subject if of interest to you, here are some other publications you might like to check out: The Phantom Museum: And Henry Wellcome's Collection of Medical Curiosities

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

"Transi de René de Chalon," Ligier Richier, 1547

A Morbid Anatomy reader sent me a wonderful image of this transi (or tomb figure depicting the decaying cadaver of the deceased) sculpted by Ligier Richier in 1547.

This fantastic figure, displayed in the Saint-Étienne church in the city Bar-le-Duc in France, once held the heart of its subject-- René de Chalon, Prince of Orange--in its raised hand, like a reliquary. The prince died at age 25 in battle following which, depending on which story you believe, either he or his widow requested that Chalon portray him in his tomb figure as "not a standard figure but a life-size skeleton with strips of dried skin flapping over a hollow carcass, whose right hand clutches at the empty rib cage while the left hand holds high his heart in a grand gesture" (Medrano-Cabral) set against a backdrop representing his earthly riches. Alas, the sculpture no longer contains Chalon's heart; it is rumored to have gone missing sometime around the French revolution.

Thanks, Pierre, for bringing this to my attention.

Vanitas Figure, Wellcome Collection, London

While in the UK the last few weeks, I had the immense pleasure of visiting the Wellcome Collection. I could not recommend this museum more highly; it was the most exciting museum I have visited in a long while. More images and a more complete review to come, but for now, as I sort through my scores of photographs, please accept my offering of this beautiful wax, cloth, and hair vanitas figure, probably made in Europe in the 18th century, on display in the Medicine Man exhibit, and is on loan from the Science Museum. More to come soon--I promise!

Friday, September 5, 2008

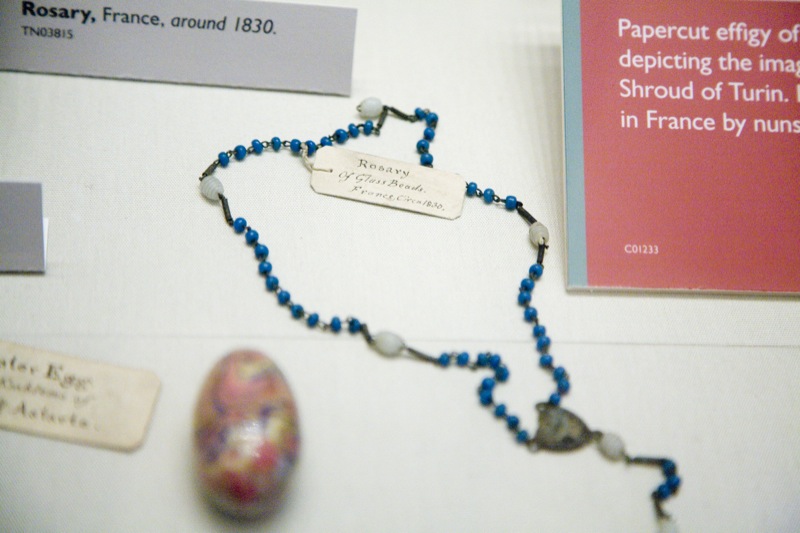

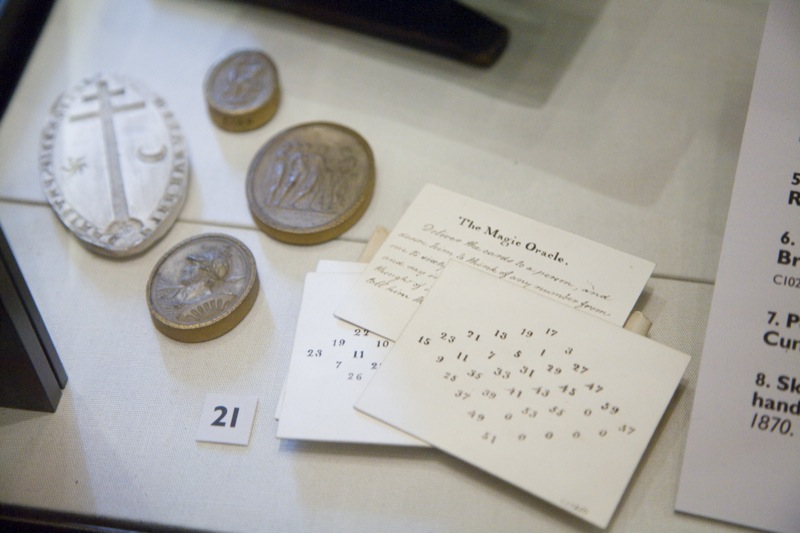

The Cuming Museum, London, England

A few days ago I visited The Cuming Museum based on a write-up I had found in my travel bible Weird Europe.

A later addition to the museum was Edward Lovett's collection of Superstious Objects, donated to the musuem in 1916; sadly, there was very little from that part of the collection on display. Still, the museum is well worth a visit if you are in the neighborhood; it provides a nice illustration of older forms of collecting, and features an intriguing assortment of objects, many embellished by their original meticulously hand-lettered labels (see third and fourth image down.)

Find out more about the museum here. See more photographs from the museum here.

In London!

My apologies for being remiss on my posting. I am in London on vacation, doing typical tourist things like visiting "The Lady of Shalott" (1888, John Waterhouse) at the Tate Britain. More to come soon--I promise!

Monday, September 1, 2008

Zoe Beloff "The Somnambulists," September 2-October 4 at Bellwether Gallery

One of my favorite contemporary artists, Zoe Beloff, is having an reception for her show "The Somnambulists" at Bellwether Gallery this Saturday night from 6-8 PM. The show itself opens tomorrow, September 2nd, and continues through October 4th. Do not miss this chance to see Beloff's haunting and uncanny work! I had the good fortune to see these works before they went on display, and they were wonderful, in the true sense of the world; her miniature theaters containing what appear to be the ghosts of dead hysterics are some of my absolute favorite pieces of contemporary art ever--they are everything I always wanted art to be and am usually disappointed that it is not.

From the Bellwether website:

The Somnambulists is comprised of five hand-painted miniature wooden theaters, into which moving images are projected. The largest of these theaters will house two high-definition 3-D color video projections of vaudevillian musical dramas: A Modern Case of Possession, and History of a Fixed Idea. Shot stereoscopically, the films depict three-dimensional figures, approximately one fifth of human scale, that appear to perform on stage with an effect closer to hallucination than projection. The installation centers on the idea of literally staging the unconscious as a hysterical drama. For these films, Beloff was inspired by several remarkable developments at the end of the 19th century: the discovery of the unconscious by psychotherapists, doctors’ emerging practice of filming their hysterical patients with motion picture cameras, and the public’s fascination with madness which manifested itself in the emotive, hysterical behavior of actors in Parisian cabarets.

Both A Modern Case of Possession and History of a Fixed Idea are based upon 19th century case histories written by the famous French psycho-pathologist Pierre Janet. In each, an actor representing Dr. Janet acts as a kind of narrator, leading us through scenes in which his patients express their delusions through song. Janet realized that his patients’ hysterical attacks provided a window, visual and auditory, into the unconscious working of their minds. Aware that they could neither hear nor speak to him in the throes of their delirium, Janet discovered that he could communicate by entering their imaginary world, as a second actor. It was as if he had walked into their mental theaters and as a master of ceremonies, was able to alleviate the fears that manifested themselves as grotesque, monstrous creatures.

In addition to these films Beloff will present four miniature theaters housing depictions of actual hysterics filmed by doctors in Belgium, Romania, and the United States. Updating a Victorian stage trick called “Pepper’s Ghost”, Beloff has transformed these patients into ghostly figures performing an endless loop of madness within the space of each diorama. Beloff will also display a new print which contains her illustrations of the theaters and various players, and outlines the acts and scenes of History of a Fixed Idea.

Beloff’s book, The Somnambulists: A Compendium of Source Material, which was published by Christine Burgin and includes a DVD, points to the complex interweaving of concepts from psychology, literature, performance, visual art, and moving-image technology at the turn of the last century. The text begins with an introduction to the “players”, with brief biographies of the scholars, artists, and performers who appear within the volume. Acting as a kind of index to Beloff’s artistic pursuits, her book provides an in-depth understanding of the range of ideas that form the basis of this exhibition.

Find out more about the show here. Find out more about Beloff's work here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)