Kristin Hussey--Assistant Curator of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons

with responsibility for the Odontological Collection--has kindly agreed

to write a series of guest posts for Morbid Anatomy about some of the

most curious objects in her collection.

The fifth post from that series follows; you can view all posts in this series by clicking here.

Images:

Henry Morton Stanley’s human tooth necklace and his infamous last African Expedition (1886-1889)

Of all the museum objects related to teeth, human tooth necklaces hold an enduring fascination. The Odontological Collection contains one such necklace associated with one of the most infamous colonial explorers, Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904). Stanley was a Welsh-born journalist who is remembered as a controversial figure for his expedition to find Scottish explorer David Livingstone and his role in the exploitation of the Congo, on behalf of King Leopold II of Belgium. In 1886, Stanley set out on what was to be his last African expedition from which he returned with the human tooth necklace and the idea for his book In Darkest Africa.

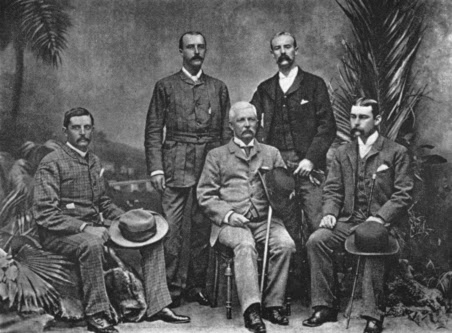

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition was organised in 1886 with Stanley at its head to rescue Eduard Schnitzer (known as Emin Pasha), the Governor of the Egyptian Province of Equatoria who was thought to be trapped by the Mahdist uprising. The trip took three years and was met by constant set back and controversy. While Stanley travelled ahead with the ‘Advance Column’ (Figure 1), a large proportion of the expedition was left behind to form a part of the ‘Rear Column’ which dissolved into violence, desertion and illness. Emin Pasha was eventually located and reluctantly brought to the East Coast city of Bagamoyo in 1889. Inspired by his journey, Stanley wrote In Darkest Africa (1890). Upon his return to England, Stanley and the surviving members of the Expedition initially received acclaim, although they later faced criticism for the numbers of deaths incurred by the party.

This necklace, composed of 34 human teeth held by braided fibres, was donated to the Museum of the Odontological Society in November 1890 by R.H. Woodhouse accompanied by a letter from Stanley himself. Stanley reported that the necklace was taken from a fallen warrior after a fight between his party and a tribe on the Ituri River. The necklace was brought back to England as evidence of the cannibal tribes Stanley claimed to have encountered on his expeditions into the Congo. In their discussions, the members of the Odontological Society were particularly interested in the prevalence of caries, or tooth decay, in the teeth of the necklace. Tooth decay was thought at the time to be a disease of what they referred to as the ‘civilised world’ due to its association with sugar. The President noted in the Transactions of the Society that such human tooth necklaces were commonly known to be worn as trophies. The teeth for this necklace were reportedly obtained by burning the skulls of vanquished enemies.

Many museum collections contain human tooth necklaces brought back by colonial explorers who used them as evidence of cannibalistic practices amongst the tribes they encountered. Although certain indigenous groups in this region and elsewhere in the world such as the South Pacific performed cannibalistic rituals, the connection with tooth necklaces is not as clear. The cultural meanings of human tooth necklaces are complex. Some scholars consider them to be prestige items in which power from slain enemies or ancestors is passed to the wearer. Human and animal teeth have been used in cultures around the world in personal ornamentation to indicate status, wealth or for medical purposes such as charms to ward off tooth-ache.

Images:

- H.M. Stanley and the officers of the Advance Column, Cairo, 1890. Wikicommons

- Necklace of human teeth brought back from the Congo region by H.M. Stanley, RCSOM/M 4.2. Copyright the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons

- Meeting the Rear Column at Banalya, In Darkest Africa (1890) Wikicommons.