I just finished reading a review of a new book about Henry Wellcome, late-19th/early 20th Century pharmaceutical magnate and maniacal collector, man behind the beloved and much-discussed on this blog

Wellcome Collection. The book, entitled

An Infinity of Things and written by Frances Larson, bills itself as "the biography of a collection" rather than a biography proper; I can think of no better collection to be given a biography of this sort, for, of all the collections I have read about, Wellcome's is certainly the most fascinating.

Before his lonely demise in 1936, Wellcome's collection--spanning the history of medicine in the broadest of possible senses-- totalled "around 1.5 million books and objects, dwarfing those of Europe's most famous museums."[

1] He collected with a kind of

William Randolph Hearst-esque zeal, drive, and folly. An extraordinarily rich man, he had in his employ agents all around the world purchasing lots for his collection; one imagines a constant stream of crates arriving from all around the globe, with employees shuffling the boxes--un-opened and un-cataloged--into warehouses where they sat until his death.

Viewing the remnants of his collection today--as one is invited to do at the Wellcome Collection's "

Medicine Man" and in the

"Science and Art of Medicine Galleries" at the Science Museum--one sees a dizzying, discipline-defying accumulation of artifacts ranging from erotica to artworks, prosthetics to votives, vanitas to dentures, shrunken heads to Napoleon's toothbrush, Darwin's walking stick (second image down) to condoms, trepanation devices to glass eyes, and much, much more (images and more

here and

here). Wellcome's collection methodology begins with the history of medicine but then extends beyond those traditional boundaries to the acquisition of any and all objects relating to the life, death, health, culture, and beliefs of "mankind."

Ultimately, this broadening interest in the artifactual history of mankind led Henry Wellcome to attempt to establish a "Museum of Man," intended to be a "...reconstruction of every stage in humankind’s development by means of objects....to form a three-dimensional book presenting an all-encompassing history of humankind’s fight for survival through the ages." [

2] The creeping scope of Wellcome's collection--from the history of medicine to the whole of humanity--beautifully illustrates a truism about the history of medicine which, I believe, is at the heart of what makes it such a rich and fascinating vein to such a wide audience. Namely, when one begins to follow the path of the history of medicine, it quickly becomes clear that it is difficult to find where the path ends; in fact, it extends out in a series of networks to every discipline relating to mankind--anthropology, archeology, literature, philosophy, psychology, art history, intellectual history, religious studies... The history of medicine--which is really the history of our attempts to hold death and disease at bay--

is, in fact, the history of humanity. Wellcome explored this with notion with great gusto via his magnificent collection, and his legacies--the

Wellcome Collection, the

Wellcome Library and the

Wellcome Trust--carry on his passion, inspiring a new generation. I can't wait to read this book and learn more about the man and his collection!

Here is some more about the book, from the review on the

New Scientist website:

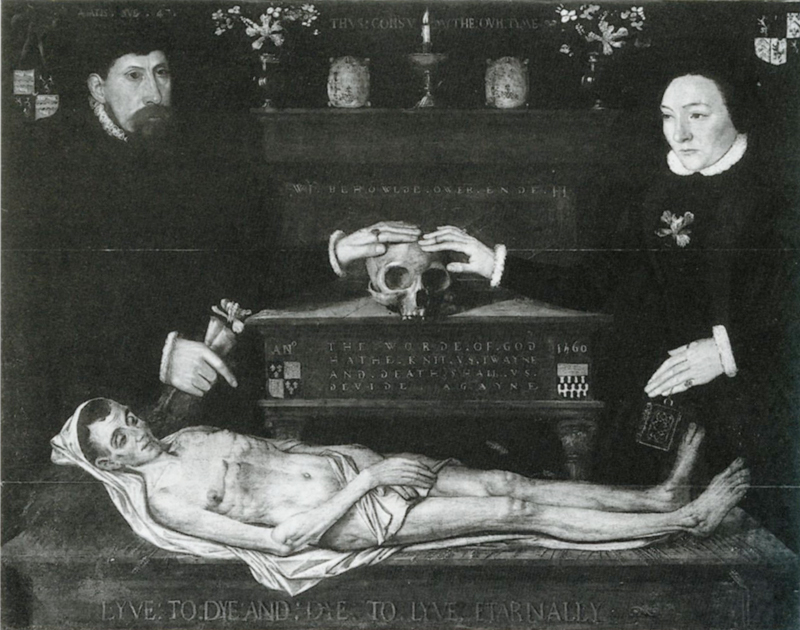

Cooper's painting [see top image] was part of a series commissioned by the pharmaceutical entrepreneur Henry Wellcome for his museum of medical history, which opened in 1913. Like other objects there, it was a mixture of the real and the fake. "Part science, part obsession, part research, part entertainment, part benefaction, part self-promotion: Wellcome's great Historical Medical Museum was always more of a fantasy than a reality," writes Frances Larson in An Infinity of Things.

Wellcome was born in a Wisconsin log cabin in 1853. By the time he died in 1936, grudgingly admired but unloved, he was a millionaire, knight, and the owner of a grotesquely overwhelming collection of objects from around the globe. Largely uncatalogued in various warehouses in London, virtually none of it was exhibited, despite his dream of building a "complete" museum on the history of illness and health. Today, it is mostly dispersed through the UK's museums, with a selection on elegant display at the Wellcome Collection in London.

Accurately billed not as a biography but as "the biography of a collection", the book is penetratingly honest. In places it reads as a gripping story of a bit of a monster, but Larson is too much the fastidious scholar - and too little the imaginative writer - to sensationalise the material. So the story is muted, along with the iniquity. She notes Wellcome's "boundless curiosity", which is evident in his collection, but what she documents is his boundless and ruthless acquisitiveness. One chapter is titled "The whole of India should be ransacked" - a quote from Wellcome's instructions to his collector in India. By the end, one feels rather sickened at the futility of his avarice.

Read the entire review (and check out photo-gallery, from which above images are drawn) by clicking

here. To pre-order the book from Amazon, click

here.

If Wellcome and his curious collection are of interest to you, you might want to visit these previous posts:

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10. You might also want to check out the book

Medicine Man: The Forgotten Museum of Henry Wellcome, a great and very visual introduction to the man and his collection; click

here to find out more. You can also visit the Wellcome Collection website by clicking

here, the Wellcome Library collection by clicking

here, and the Wellcome Trust website by clicking

here. You can also read more about the life and collection of Wellcome by clicking

here.

Image captions, top to bottom:

1) Chloroform. This 1912 watercolour painting by Richard Tennant Cooper shows demons with surgical instruments attacking an unconscious man on an operating table. It conveys fears of the vulnerability that accompanies the many benefits of surgery under anaesthetic. (Image: Wellcome Library)

2) Darwin's walking stick. This walking stick, made from whalebone with an ivory skull pommel and green glass eyes, belonged to Charles Darwin. It was made at some point between 1839 and 1881. (Image: Wellcome Library)

3) Glass eyes. Fifty glass eyes stare out of this case, made around 1900, possibly by E. Muller of Liverpool, UK. (Image: Wellcome Library)