Anatomical Venus from the Spitzner Collection, demountable in 40 parts. 19th century, wax; Montpelier, Museum of the Faculty of Science.

Click on image to see larger, more detailed image.

Found here via Elettrogenica.

Documenting the Invisible: Spiritualism, Lily Dale, and Talking to the DeadYou can find out more about this event here. You can get directions to Observatory--which is next door to the Morbid Anatomy Library (more on that here)--by clicking here. You can find out more about Observatory here, join our mailing list by clicking here, and join us on Facebook by clicking here.

An illustrated lecture by photographer Shannon Taggart

Date: Tuesday, August 31

Time: 8:00 PM

Admission: $5

Presented by Morbid Anatomy

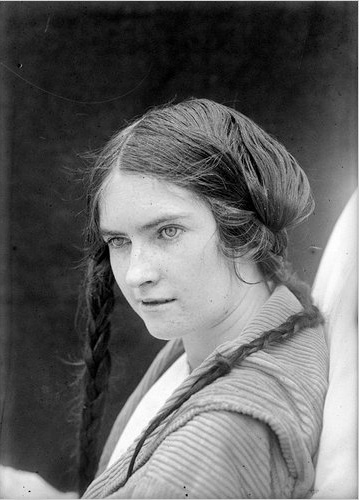

Spiritualism is a loosely organized religion based primarily on a belief in the ability to communicate with spirits of the dead. The movement began in upstate New York in 1848 when two young girls named Margaret and Kate Fox claimed to be in contact with the spirit of a dead peddler buried beneath their home. Photographer Shannon Taggart first became aware of Spiritualism as a teenager when her cousin received a reading in Lily Dale, NY, The World’s Largest Spiritualist Community. A medium there revealed a strange family secret about the death of their grandfather that proved to be true. Taggart became deeply curious about how someone could possibly know such a thing.

Thus began a five year photography project focused on Modern Spiritualism. During her image making she immersed myself in the history and philosophy of Spiritualism, had more readings than she can count, experienced spiritual healings, took part in séances, attended a psychic college and sat in a medium’s cabinet, all with her camera. Despite this exposure she finds herself no closer to any definitive answer of what it all means. She feels as if she has peered into a mystery.

Shannon Taggart is a freelance photographer based in Brooklyn, New York. She received her BFA in Applied Photography from the Rochester Institute of Technology. Her images have appeared in numerous publications including Blind Spot, Tokion, TIME and Newsweek. Her work has been recognized by the Inge Morath Foundation, American Photography, the International Photography Awards, Photo District News and the Alexia Foundation for World Peace, among others. Her photographs have been shown at Photoworks in Brighton, England, The Photographic Resource Center in Boston, Redux Pictures in New York, the Stephen Cohen Gallery in Los Angeles and most recently at FotoFest 2010 in Houston. For more about Shannon Taggart, visit www.shannontaggart.com.

It’s Scotland Jim, But Not As We Know it: The W.D. Trotter Anatomy Museum - A Brief HistoryYou can find out more about this presentation here. You can get directions to Observatory--which is next door to the Morbid Anatomy Library (more on that here)--by clicking here. You can find out more about Observatory here, join our mailing list by clicking here, and join us on Facebook by clicking here.

An illustrated lecture and virtual tour by Chris Smith, Curator of the W.D. Trotter Anatomy Museum, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Date: Friday, August 27

Time: 8:00 PM

Admission: $5

Presented by Morbid Anatomy

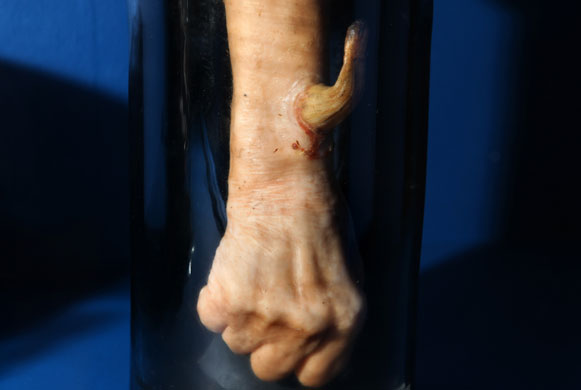

Tonight, Chris Smith, curator of the W.D. Trotter Anatomy Museum of the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, will give a brief history of the Museum, its collections and the role it plays today. As part of the southern-most Medical School in the world, this isolation can be both a hindrance as well as of benefit; but with its foundation built upon a strong Scottish heritage, the traditions of Anatomical Teaching have been sustained and continue to strengthen in this proud institution. From the early plaster, wax and papier-mâché through to todays technologies of 3D imaging and plastination, you will be given a whirlwind tour of this collection and some of the personalities responsible for its creation and development over the last 135 years.

Chris Smith is a trained Secondary School Teacher with 10 years experience in teaching and education and a passion for the collection, teaching and preservation of history. Chris changed gears in 2005 to take up the role as Anatomy Museum Curator and Anatomy Department Photographer at the University of Otago. In this role Chris has maintained and further developed the use of anatomical specimens, both historic and modern, for teaching and research, as well as increasing public awareness of the collection and the history of the museum and department. In 2007 and 2008 he traveled to Thailand as part of the Bio-archaeology team to excavate and photograph human remains at Ban Non Wat (Origins of Angkor Project), a prehistoric Neolithic to Iron Age site. He regularly attends conferences within New Zealand and neighboring Australia, visiting institutions and collections and in 2008 received a Queen Elizabeth the 2nd (QEII) Technicians’ Study Award, which enabled him to visit institutions and collections in United Kingdom and attend the European Association of Museums of the History of Medical Science Congress held that year in Edinburgh. It was at this event that he and Joanna crossed paths and as such with a visit to meet new family in the US in 2010 and making contact with Joanna, he has been put in this privileged position of being able to share a little about ‘his’ museum.

The last decade has revealed a burgeoning interest and fascination with human skin, particularly among philosophers, writers, artists and designers. Meanwhile, regenerative medicine has seen major advances in the development of artificial skin designed to improve the structure, function and appearance of the body surface that has been damaged by disease, injury or ageing. So there couldn't be a better time to get under the surface of this subject.--Lucy Shanahan, Wellcome Collection Curator and co-curator of 'Skin'I have been hearing excellent reports from scores of people about the new Wellcome Collection exhibition entitled, simply, 'Skin.' Sadly, I will not be able to see it in person (as it closes on September 2th), but the images above--most drawn from the exhibition website--and the web exhibition text make it clear that the Wellcome has done it again: a thoughtful, broadly considered, and lovely investigation and survey into the science, meaning, art, and implications of the notion of 'skin.'

The skin is our largest organ. It gives us a vital protective layer, is crucial for our sense of touch and provides us with a highly sensitive and visible interface between our inner body and the outside world. Spots, scars, moles, wrinkles, tans and tattoos: the look of skin can reveal much about an individual's lifestyle, health, age and personality, as well as their cultural and religious background. The skin is also remarkable for its ability to regenerate and repair itself.For more about the exhibition including hours and visiting information, visit the Wellcome Collection website by clicking here. You can visit the image galleries--from which most of the above images were pulled and which contain many more riches--by clicking here.; Credits and captions for images follow. Also, if you are, like me, a fan of the Wellcome and its work, you won't want to miss tonight's lecture at Observatory featuring Wellcome Collection curator Kate Forde; click here for more on that.

The multidisciplinary exhibition 'Skin' takes a predominantly historical approach, beginning with early anatomical thought in the 16th and 17th centuries, when, for anatomists, the skin was simply something to be removed and discarded in order to study the internal organs. The story continues through the 18th and 19th centuries and approaches its conclusion in the 20th century, by which time the skin was considered to be of much greater significance and studied as an organ in its own right.

The exhibition will incorporate early medical drawings, 19th-century paintings, anatomical models and cultural artefacts juxtaposed with sculpture, photography and film works by artists including Damien Hirst, Helen Chadwick and Wim Delvoye.

The 'Skin' exhibition will be complemented by the 'Skin Lab', which features artistic responses to developments in plastic surgery, scar treatments and synthetic skin technologies, including two newly commissioned works by the artists Rhian Solomon and Gemma Anderson. Visitors are invited to participate in an interactive and sensory experience - experimenting with skin-flap models used in plastic surgery, trying on latex skin-suits or studying biological jewelery.

Exquisite Bodies: or the Curious and Grotesque History of the Anatomical ModelYou can find out more about this presentation here; As mentioned above, you can find out more about the exhibition here, here and here and see a preview of the lecture here. You can get directions to Observatory--which is next door to the Morbid Anatomy Library (more on that here)--by clicking here. You can find out more about Observatory here, join our mailing list by clicking here, and join us on Facebook by clicking here.

An illustrated lecture by Wellcome Collection Curator Kate Forde

Date: Thursday, August 26

Time: 8:00 PM

Admission: $5

Presented by Morbid Anatomy

Tonight, Kate Forde of London’s Wellcome Collection will deliver an illustrated lecture detailing the rise and fall of the popular anatomical museum in 19th century Europe as detailed in The Wellcome’s recent ‘Exquisite Bodies’ exhibition.

The ‘Exquisite Bodies’ exhibition, which was curated with the assistance of Morbid Anatomy’s Joanna Ebenstein, was inspired by the craze for anatomy museums and their artifacts–particularly wax anatomical models–in 19th century Europe. In London, Paris, Brussels and Barcelona displays of wax models became popular with visitors seeking an unusual afternoon’s entertainment. The public were invited to learn about the body’s internal structure, its reproductive system and its vulnerability to disease–especially the sexually transmitted kind–through displays that combined serious science with more than a touch of prurience and horror.

At a time when scandal surrounded the practice of dissection, the medical establishment gave these collections of human surrogates a cautious welcome; yet only a few decades later they fell into disrepute, some even facing prosecution for obscenity. This talk will trace the trajectory of these museums in a highly illustrated lecture featuring many of the historical artifacts featured in the show.

To find out more about the exhibition ‘Exquisite Bodies,’ click here and here.

Kate Forde is Curator of Temporary Exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection, London. She is interested in the role of museums in the shaping of cultural memory and in the display of fine art within science-based institutions. Her current research is taking her from the great dust-heaps of Victorian London to Staten Island’s landfill Fresh Kills for an exhibition with the working title ‘Dirt’. You can see a preview of tonight's lecture by clicking here.

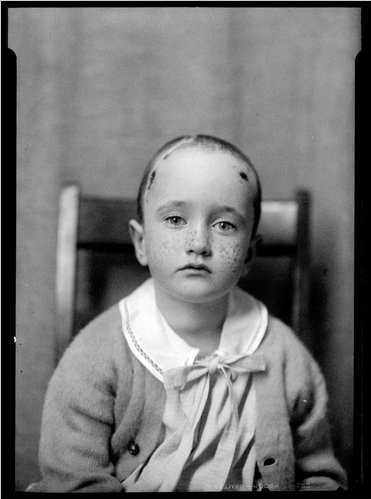

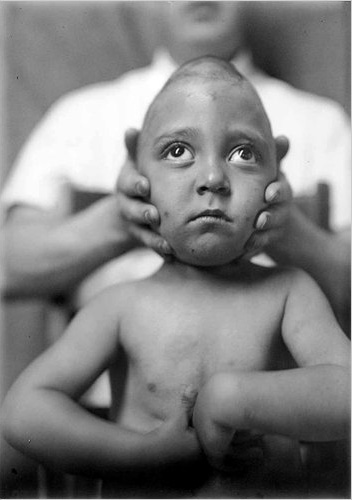

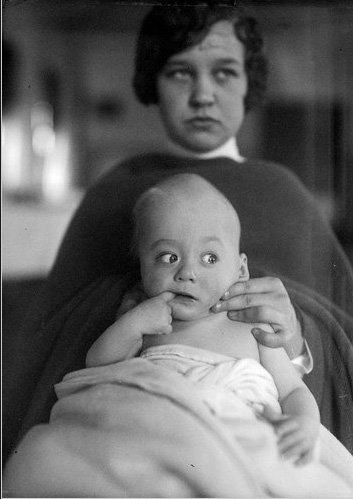

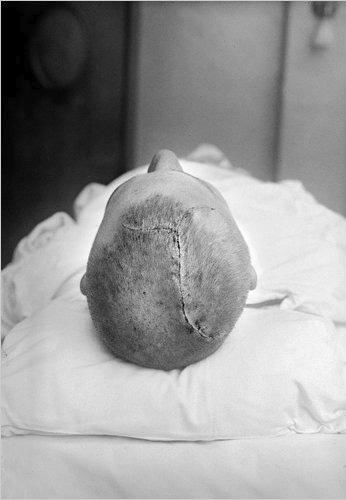

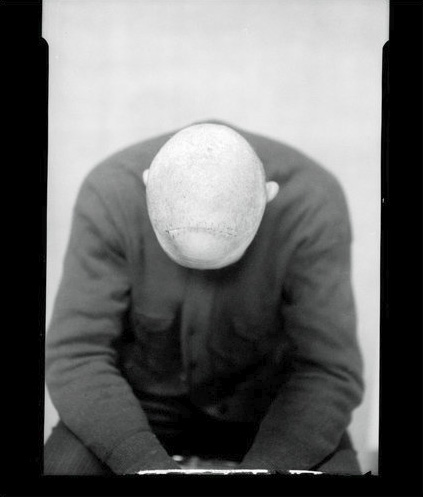

The cancerous brains were collected by Dr. Harvey Cushing, who was one of America’s first neurosurgeons. They were donated to Yale on his death in 1939 — along with meticulous medical records, before-and-after photographs of patients, and anatomical illustrations. (Dr. Cushing was also an accomplished artist.) His belongings, a treasure trove of medical history, became a jumble of cracked jars and dusty records shoved in various crannies at the hospital and medical school.You can read the full article by clicking here, and view the entire image slide-show--from which many of the above images were drawn--by clicking here. The Cushing/Whitney Medical Library at Yale University is located at 333 Cedar Street, New Haven and is open to the public Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; and Sunday, 9:30 a.m. to 8 p.m. (203) 785-5352. You can find out more about visiting the collection by clicking here.

Until now. In June 2010, after a colossal effort to clean and organize the material — 500 of 650 jars have been restored — the brains found their final resting place behind glass cases around the perimeter of the Cushing Center, a room designed solely for them....

Most of the jars contain a single brain; a few hold slices of brains from several patients. Some postoperative photographs next to the jars show patients with tumors bulging from their heads. When Dr. Cushing could not remove a tumor, he would remove a piece of the skull so the tumor would grow outward rather than compress the brain. It was not a cure, but it relieved the patient of many symptoms.

"Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater, 1930 to 1960"You can find out more about these presentation here. You can get directions to Observatory--which is next door to the Morbid Anatomy Library (more on that here)--by clicking here. You can find out more about Observatory here, join our mailing list by clicking here, and join us on Facebook by clicking here.

An Illustrated Lecture and artifact demonstration by Eric P. Nash, author of Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater

Date: Monday, August 23rd

Time: 8:00

Admission: $5

Presented by Morbid Anatomy and part of the Oxberry Pegs Presents series

*** Please note: Books will be available for sale and signing and authentic kamishibai theatre will be available to view

Before giant robots, space ships, and masked super heroes filled the pages of Japanese comic books–known as manga–such characters were regularly seen on the streets of Japan in kamishibai stories. Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater tells the history of this fascinating and nearly vanished Japanese art form that paved the way for modern-day comic books, and is the missing link in the development of modern manga.

During the height of kamishibai in the 1930s, storytellers would travel to villages and set up their butais (miniature wooden prosceniums) on the back of their bicycles, through which illustrated boards were presented. The story boards–colorful, hand-painted, original art drawn with the great haste that signifies manga, glued on cardboard and lacquered to protect them in the rain–told stories ranging from action-packed westerns to science-fiction stories to ninja tales to monster stories to Hiroshima stories to folk tales and melodramas for the girls. Golden Bat, a supernatural, cross-eyed, skull-faced superhero; G-men; Cinderella; the Lone Ranger; and even Batman and Robin starred in kamishibai stories. The storytellers acted as entertainers, acting out the parts of each character with different voices and facial expressions, and sometimes too, they became reporters, when the stories were the nightly news reports on World War II. Kamishibai was so popular and widespread, that when television hit Japan in the mid-1950s, it was known as denki kamishibai–electric paper theater.

Tonight, author Eric P. Nash will tell the story of kamishibai as detailed in his gorgeous new book Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater. He will also bring in a genuine kamishibai set from the 1930s and make copies of his book available for sale and signing.

Eric P. Nash has been a researcher and writer for the New York Times since 1986. He is the author of several books about art, architecture, and design, including Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater, MiMo: Miami Modernism Revealed, and The Destruction of Penn Station. His work has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The San Francisco Chronicle and Discover magazine.

Still Life: The Art of AnatomyYou can find out more by clicking here or here.

Saturday, 10 July 2010 - 12 September 2010

Dunedin Public Art Gallery

Dunedin, New Zealand

Noted Dunedin based filmmaker and medical doctor Paul Trotman, has worked closely with the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in researching Dunedin's rich collections towards the realization of Still Life: The Art of Anatomy. This exhibition brings together an array of historical and contemporary items, such as Dr John Halliday Scott's elegant anatomical drawings and old master prints, through to porcelain and wax casts of aspects of the body and the latest interactive computer generated 3D anatomical models. Still Life provides a stunning insight into this complex subject and also reveals the important lineage that science and art shares through the analysis, distillation and depiction of the human form.

"Angels, Animals and Cyborgs: Visions of Human Enhancement"

"Angels, Animals and Cyborgs: Visions of Human Enhancement" "Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater, 1930 to 1960"

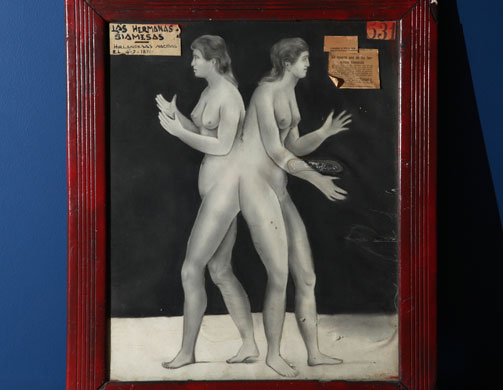

"Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater, 1930 to 1960" Hermaphrodites: Sex Undetermined

Hermaphrodites: Sex Undetermined Exquisite Bodies: or the Curious and Grotesque History of the Anatomical Model

Exquisite Bodies: or the Curious and Grotesque History of the Anatomical Model It’s Scotland Jim, But Not As We Know it: The W.D. Trotter Anatomy Museum - A Brief History

It’s Scotland Jim, But Not As We Know it: The W.D. Trotter Anatomy Museum - A Brief History Animators The Brothers Quays Have Watched and Other Likely Things

Animators The Brothers Quays Have Watched and Other Likely Things Documenting the Invisible: Spiritualism, Lily Dale, and Talking to the Dead

Documenting the Invisible: Spiritualism, Lily Dale, and Talking to the Dead