Augustine included curiositas in his catalog of vices, identifying it as one of the three forms of lust (concupiscentia) that are the beginning of all sin (lust of the flesh, lust of the eyes, and ambition of the world). The overly curious mind exhibits a “lust to find out and know,” not for any practical purpose but merely for the sake of knowing. Thanks to the “disease of curiosity” people go to watch freaks in circuses and charlatans in the piazzas. Augustine saw no essential difference between such perverse entertainments and the “empty longing and curiosity [that is] dignified by the names of learning and science.”I just came across a nice meditation on the history of the debate of curiosity as value or vice on the website of Author William Eamon, author of Science and the Secrets of Nature and The Professor of Secrets: Mystery, Medicine, and Alchemy in Renaissance Italy:

The Disease Called CuriosityYou can read this piece in its entirety--and find out more about William Eamon and his work-- by clicking here.

Nowadays we think of curiosity as an emotion necessary for the advancement of knowledge, indeed as the well-spring of scientific discovery. It was not always so.

Saint Augustine, in the fourth century, stated the traditional medieval view of curiosity, and it wasn’t favorable. In the Confessions, the Bishop of Hippo made inquisitiveness in general the subject of a vicious polemic, thereby setting the tone for the debate over intellectual curiosity for centuries. Augustine included curiositas in his catalog of vices, identifying it as one of the three forms of lust (concupiscentia) that are the beginning of all sin (lust of the flesh, lust of the eyes, and ambition of the world). The overly curious mind exhibits a “lust to find out and know,” not for any practical purpose but merely for the sake of knowing. Thanks to the “disease of curiosity” people go to watch freaks in circuses and charlatans in the piazzas. Augustine saw no essential difference between such perverse entertainments and the “empty longing and curiosity [that is] dignified by the names of learning and science.”

No difference between gawking at freaks in a sideshow and making investigations in natural philosophy? That’s what the saint said: “From the same motive,” Augustine wrote, “men proceed to investigate the workings of nature, which is beyond our ken—things which it does no good to know and which men only want to know for the sake of knowing.” Augustine’s severe judgment of intellectual curiosity, linking it with the sin of pride, the black arts, and the Fall, became conventional in medieval thought. In the Renaissance, it gave rise to such memorable characters as Doctor Faustus, who bartered his soul to the devil to satisfy his insatiable curiosity and quest for power.

Yet gawking curiosity was the perpetuum mobile of Renaissance science. Early modern curiosity was insatiable, never content with a single experience or object. Whereas Augustine linked curiosity to sensual lust and human depravity, Renaissance natural philosophers saw it as being driven by wonder and the engine of discovery...

...Venice’s maritime empire and its rich craft tradition provided plentiful fuel for wonder and curiosity. The continual contact with exotic commodities, whether herbs from the New World, mechanical toys from Persia, or fake dragons and basilisks, fueled Renaissance curiosity. All that evoked curiosity and wonder became prized objects for collectors, who displayed rare and exotic natural and artifical objects in curiosity cabinets, like peacocks proudly displaying their colorful feathers—indeed, peacock feather, too, were prized objects for collectors.

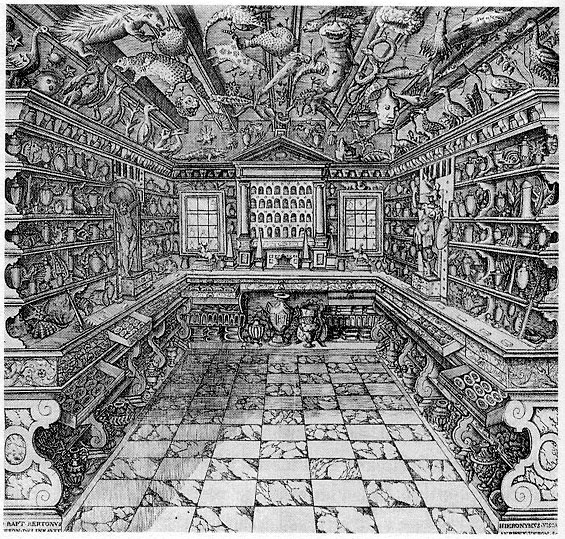

Pharmacies displayed the curiosities of Renaissance culture. The cabinet of pharmacist Francesco Calzolari at Verona, pictured here, displayed dried herbs, minerals, preserved animals, birds and snakes, including a supposed unicorn horn.

Such objects would become the “curious” things of early modern science. Saint Paul’s admonition, Noli alta sapere, “Do not seek to know high things,” gave way in the Renaissance to Horace’s more hopeful Sapere aude, “Dare to know.”

The transformation of curiosity in the Renaissance was a precondition of modernity. Without curiosity, there can be no scientific discovery, and without discovery, there can be no new knowledge.

Image caption: Pharmacies displayed the curiosities of Renaissance culture. The cabinet of pharmacist Francesco Calzolari at Verona, pictured here, displayed dried herbs, minerals, preserved animals, birds and snakes, including a supposed unicorn horn.

3 comments:

wonderful post, happy to be prone to the dangers and pleasure of curiosity

I know my curiosity has gotten me into a bind a time or three.

Este asunto me recuerda la curiosidad de Adán y Eva, y cómo esto se relaciona con el pecado...

Post a Comment