Following, please find one more guest post in which Evan Michelson (2nd photo, right hand side) of "Oddities" fame documents our recent trip through Italy researching the history of the

preservation and display of the human corpse.

Here, her response to the amazing Florence pathology museum, or the "Museo di Anatomia Patologica dell'Universitá degli Studi di Firenze"; interestingly, the fine and senstivie pathological waxes you see here were made in the early 19th century by the la Specola workshop, which also brought us Clemente Susini's unforgettable Anatomical Venuses:

The Museo di Anatomia Patologica dell'Universitá degli Studi di Firenze is a happy example of a newly-renovated, early anatomical collection that has been well loved and cared for. The waxes, osteological preparations and wet specimens are all housed in their original, highly ornamental wood and glass display cases, making the place seem more like a treasury than a didactic collection of pain, healing and preserved suffering. Indeed some of the small, ornately jarred specimens, with their delicately handwritten labels are nearly indistinguishable from sacred relics.

The history of this collection goes back to 1824, with the founding of the Medical Society in Florence. It was always intended as a teaching tool for the medical students at the university, and the wax models here are some of the most beautiful examples of the ceroplast's art. The casts were individually commissioned by the anatomy professors and executed by some of the most renowned wax workers of Florence. The result is a 3D catalogue of benign and cancerous tumors, burns, venereal infections, abnormal growths and congenital birth defects, all rendered with the greatest loving care and verisimilitude. The full-sized wax leper could be a saint in any church, his suffering as profound as any wax Christ.

Our guide Gabriella Nesi (2nd image, left; a professor of pathology who has taken the museum under her wing) was particularly eager to point out the models of before-and-after facial reconstructive surgeries, which demonstrated the progress of 19th century plastic surgery by recording not only the sutures and healing wound sites, but the more subtle details like post-surgical stubble on a shaved head. The results are strangely intimate, and we were surprised to learn that many of these models were not only cast from actual patients, but that the museum still has most of the case histories. It is rare to know the story behind any given wax medical model - once a thing has a name, it all becomes unavoidably real.

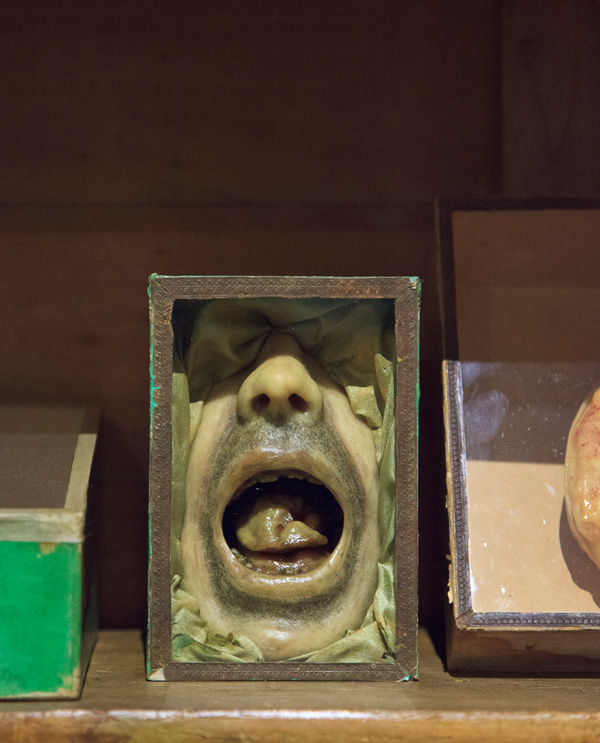

Although the wax models themselves are breathtaking, it was the presentation of some of the smaller waxes, housed in delicate paper and glass boxes, that drew our attention. These preparations, although clearly intended for a scientific audience, utilize the decorative, visual language of spiritual offerings. Indeed, many of the wax modelers of the 19th century functioned in both the religious and the didactic realm, and the result is a transcendent form of visual art that straddles the spiritual and the scientific, lending the anatomy itself an air of great mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment