I made the acquaintance of British visual artist Paul Rumsey through the administration of this blog. I have been quite taken with his work as well as his list of influences, which include some of my own favorites: Ernst Haeckel, Alfred Kubin, Francisco Goya, medical museums, Charles Baudelaire, "Belle Rosina," waxworks, Jorge Luis Borges, and many, many more. His work looks more 15th century fantasy or 19th century graphic print than anything from our own century; I mean that in the best of ways.

Paul sent me Drawing from the Imagination, a catalogue of his work. The introductory essay he authored details how he realized his own idiosyncratic artistic voice, a voice in dramatic opposition to that of his modernist-inspired teachers and colleagues. In the process, he traces the evolution of the grotesque and the fantastic in art from its birth to contemporary popular culture:

I came to see the history of art, not as separate layers of sediment or strata but as a living thing like a tree, growing with intertwining stems, alive from root to twig. My work belongs to the tradition of the grotesque and fantastic. It is possible to classify the various ways that reality is distorted in this kind of work: the mixing of forms, changes of scale, elongations, compressions and reversals, a distorted reflection which shows the world in a different light, a different perspective, the world re-imagined in a dream, subjectively influenced by the dreamer...Check out more of Paul's work here, here, and here. Read the entire introductory essay from which the above quote is pulled here.

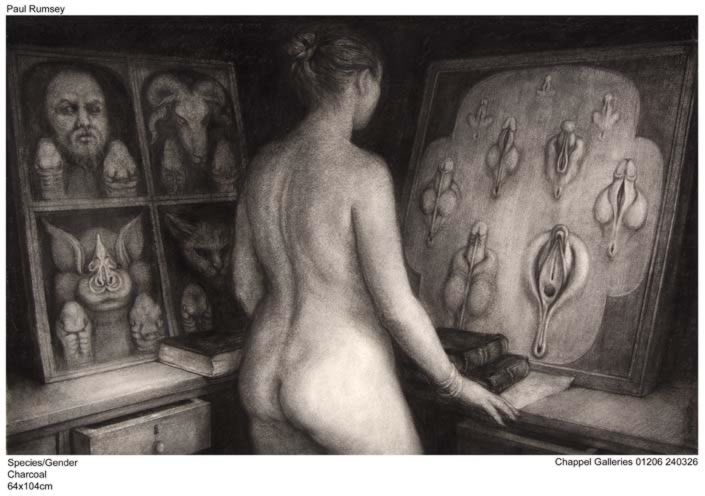

The tradition of the grotesque is particularly alive in prints. The fantastic is especially suited to the graphic medium, and it is possible to track almost its entire history in etchings, engravings and woodcuts. A fine book The Waking dream: Fantasy and the Surreal in Graphic Art, 1450-1900charts this progress through Holbein’s Dance of Death, the macabre prints of Urs Graf, the engravings of Callot, seventeenth-century alchemical prints, scientific, medical and anatomical illustration (I adapted the embryonic development diagrams of Ernst Haeckel for my drawing Species/Gender), emblems, the topsy-turvy world popular prints, Piranesi’s Prisons (which influence my architectural fantasies), Rowlandson, Gillray (whom I studied for guidance on how to draw caricature for drawings like my Seven Sins) , Goya, Fuseli and Blake, and into the nineteenth century with Grandville, Daumier, Meryon, Dore, Victor Hugo’s drawings and Redon. The tradition continues with the Symbolists and Richard Dadd, Ensor and Kubin, through to Surrealism, which recognised many of the artists of the grotesque and fantastic tradition as precursors. It is via Surrealism that much of this work has come to be appreciated. In the twentieth century this type of imagery has permeated culture, and is found everywhere, in diverse art forms including: the satiric installations of Keinholz, the drawings of A. Paul Weber, the cartoons of Robert Crumb, the animated films of Jan Svankmajer, photographs by Witkin, plays by Beckett, science fiction by Ballard, fantastic literature like Meyrink’s The Golem, Jean Ray’s Malpertuis, the art and writings of Bruno Schulz and Leonora Carrington, films by Lynch, Cronenberg and Gilliam; all are part of a spreading network of connections, the branching tentacles of the grotesque.

This is the tradition to which my work belongs, and when I am drawing I am aware of making connections with every strand of this tradition. For example, when I was working on my skeleton drawings I thought back, via zombie movies, to the thousands of animated skeletons in art, from Posada and Kubin back to Bruegel’s Triumph of Death, and back further to the scene of necromancy in Lucan’s Pharsalia from the first century CE, a scene that influenced Shelley’s Frankenstein, which in turn influenced Romero’s Day of the Dead zombie movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment